The Netflix Stock Crash - Takeaways from a Netflix Content Strategy Alum & Screenwriter

Beneath the noisy headlines lies a deeper story on the future of streaming

A behemoth stumbles

Netflix announced Tuesday, April 19th that it had lost 200K subscribers in Q1 2022, its first quarter of subscriber losses in over a decade. Wednesday, the stock plummeted by 35% and $54bn of market cap was wiped out. More pessimistically, the company predicted it would lose an order of magnitude greater number of subscribers in Q2 at 2M projected sub losses.

By any measure, this was a terrible result for the company. But are pronouncements of Netflix’s demise justified or alarmist? And what does this portend for the entertainment industry as a whole?

First, let’s contextualize where Netflix presently sits now that the dust has settled.

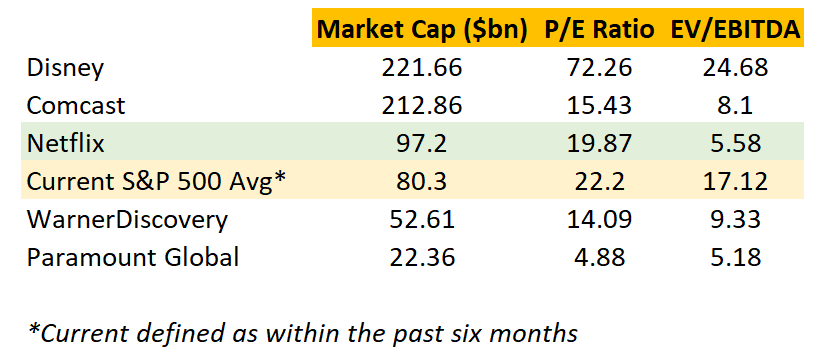

When compared to its peers in media and fellow large cap companies generally, Netflix has a P/E ratio in line with its peers and an EV/EBITDA far below the S&P average, as well as below 10 which has historically been considered strong.

I therefore posit the question: did the stock crash, or did it come back down to earth after a frothy COVID-fueled spike? Perhaps investors are taking this opportunity to re-value the company on its fundamentals vs. subscriber growth momentum.

For Netflix, the implications are very clear. EBITDA growth and margin expansion will once again rule the day, as content budgets scale back to right-size spending with revenue and ARPU becomes more important. An ad-supported tier, crackdowns on password sharing, decelerating content budgets – these all felt like inevitable changes, more a matter of when the party would be over rather than if. But these are also low-hanging fruit. What are the more material implications for Netflix and the industry at large? Beneath the noisy headlines, there is a deeper story about the future of streaming.

Streaming’s Infancy - a Bull in a China Shop

The proliferation of streaming disrupted more than just the way audiences around the world consume content - it changed the way revenues are generated by film and TV assets. The ultimates models used to forecast film profitability and the conventional deficit-financed TV model were to an extent rendered obsolete in a world where streaming services would acquire worldwide rights, including all derivative rights such as linear broadcast, in perpetuity. Whether it was the traditional deficit-financed first run TV plus domestic and international syndication model or theatrical runs supporting home entertainment and later windows for film, the “one-shot” cost-plus acquisitions in streaming replaced a complex web of revenues and associated cash waterfalls.

But a decade after the first SVOD originals launched on Netflix, as the subscriber growth story begins to slow down, studios are re-examining the thesis that drove the new status quo. Netflix famously burned cash for years as its content budget ballooned, all in service of driving subscriber growth. For a long time, this worked quite well, especially when the service launched worldwide in 2016. The thesis behind an all-in, cash-burning content investment strategy was to drive subscriber acquisition no matter the cost. Like many early stage subscription-based startups, CAC and LTV were not the focus, but rather priorities for once a subscription base had already scaled. In such an environment, acquiring all rights in perpetuity at high prices and high studio premiums made sense.

For studios, the selling environment was irresistible. But in a world of decelerated growth and tightening budgets, the underlying conditions have changed. Profitability and margin expansion are once again driving a fundamentals-based investment thesis on Wall Street, which undermines the “one-shot” acquisition model in two important ways. Firstly, streamers will no longer have the same insatiable appetite at higher prices, as content budgets narrow amid greater margin focus. And therefore secondly, studios will no longer generate the same amount of cash from these sales and will be left wondering whether streaming can match the revenues from legacy cable, theatrical and home entertainment sales.

Managing digital transformation

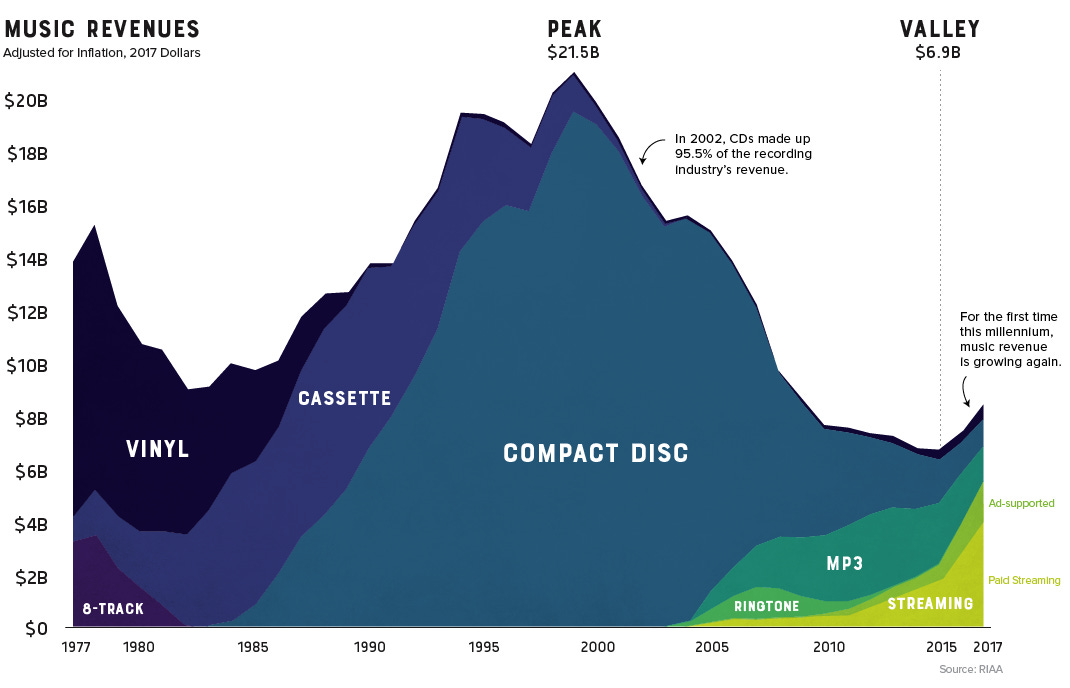

The newspaper and music industries are grave reminders of the risks that streaming and digital disruption can pose to major incumbents if the transition is not managed effectively. Taking on losses to support a strong push into streaming, all just to build a less profitable business, is the nightmare scenario facing management teams at all the large media companies. For a while, rapid subscriber growth quelled any fears. In the case of Netflix, that era seems to be over. The other large incumbents may escape this heightened scrutiny for a while longer due to the M&A consolidation frenzy that still dominates industry coverage and investment theses. But eventually, the fundamentals will reassert themselves - they always do.

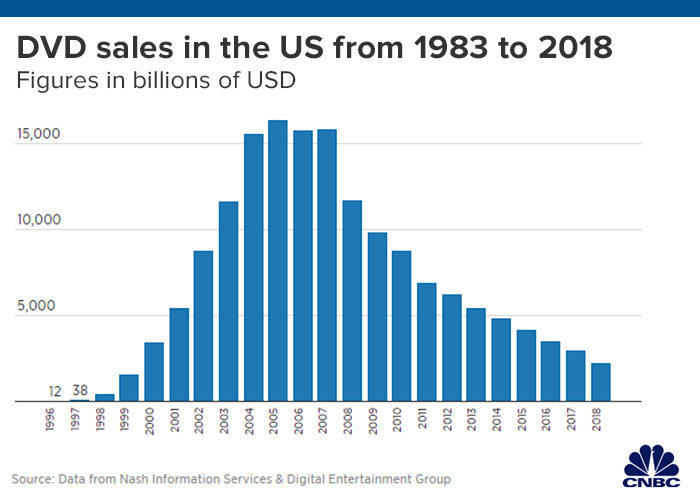

When multiples are once again based on EBITDA versus subscribers, studios and content owners will need a different approach to monetization. Or rather, an older and more familiar approach: ancillary revenues. Funneling content to in-house streaming services to drive subscriber acquisition at the exclusion of ancillary revenues will no longer maximize value the way it has in streaming’s infancy. But the ancillary revenues of this new era will not be the same as the legacy business: that model is all but dead. Home entertainment, once the golden goose of film monetization, has steadily declined since its peak 15 years ago.

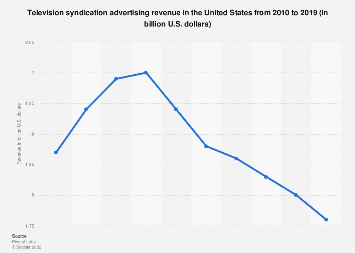

On the television side, the domestic syndication market has also declined from its peak last decade.

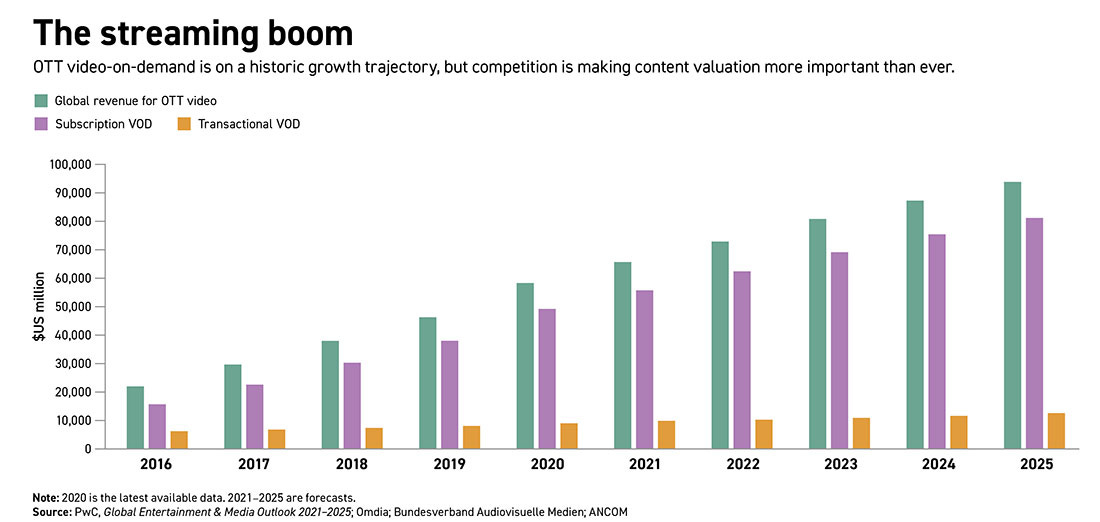

These trends are not going to reverse. Global OTT video revenues nearly tripled from 2016 to 2020 and are continuing to grow; the streaming genie cannot be put back in the bottle.

The ancillary revenues of the streaming era will be different. Rights will be cut up: SVOD, linear, AVOD, Electronic Sell-Through (EST), TVOD, and other derivative rights will be uncoupled and independent decisions will need to be made along each dimension. Exclusivity will no longer be a foregone conclusion, especially as territories are once again increasingly separated to align with the evolving strategic objectives of both buyers and sellers. Even output deals, long having trended towards the largest dollar amounts, will need to be reconsidered. Furthermore, new revenue streams may emerge as digital distribution continues to innovate, like the Free Ad-Supported TV (FAST) window.

Reinventing the wheel, or learning to fly?

Some commenters have remarked that streaming may end up becoming an ad-supported and theatrical-supported business, just like the legacy model it supplanted. But these wry observations miss some profound differences. On-demand consumption is a far better experience than linear broadcast. Even if episodes are released weekly, if you miss one you can watch the next day; you don’t have to wait several months for the DVD or a rebroadcast. And secondly, OTT replaces the massive capex and local regulatory-heavy broadcast infrastructure. The large media companies always relied on global revenues but via a middle-man heavy web of local broadcasters and distributors. That has now flattened and the potential for growth is far higher. Cars and planes both have wheels, but one can go a lot farther than the other.

What does this mean for artists and filmmakers? Back-end is back-on the menu

Despite the boom in TV output and the huge overall deals struck with TV’s top creators, writers were one of the principal casualties in the one-shot streaming model. Shows going fewer, shorter seasons, with smaller rooms, fewer on-set opportunities, and back-end buyouts shattered the previous model both for advancing in the craft and in building wealth. But with the return of ancillary revenues, artists will once again have room to bargain for their share of the waterfall. And perhaps more importantly, ad-supported models for first-run shows will once again incentivize both longer and more seasons, as ad rates will jump for hit shows whereas a subscription-only model incentivizes cancellations before season-over-season budget increases eat into overall title efficiency.

Overall buying may scale back in the immediate term, but programming for over a billion subscribers worldwide across all the various streaming platforms will nevertheless require a large volume of original content. And if shows have longer and more seasons, the net change in episodes produced per year may not be as dramatic a decline as some may fear - if it declines at all.

On the feature side, a return to ancillary revenues is good news for the theatrical model. Box office receipts contributing to recovering production costs and P&A as well as super-charging awareness and marketing for later windows makes more sense in a world where streamers prioritize revenue maximization over strict exclusivity.

The WGA demonstrated formidable resolve in its fight with the talent agencies over the practices of packaging and agency-owned production entities. It will need every bit of that resolve in future negotiations to ensure writers get their piece of the pie as the business models evolve.

Hollywood has always been a hit-driven business. But a “quality over quantity” environment encourages more investment in the artists and filmmakers creating those hits.

Reed, Ted, and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day

April 19th, 2022 was a Bad Day for Netflix. To suggest otherwise would be delusion. But the company remains healthy and poised to rebound if it executes effectively in the coming quarters, and by now, Reed Hastings has earned the benefit of doubt in rising to the challenge.

But for this member of the industry, excitement is in the air regarding the future of streaming. Act 1 is over. The status quo has been shattered and we have heeded the Call to Adventure. The twists and turns of Act 2 await, and in those twists and turns lies opportunity — for investors and artists, alike. Opportunity, and a good story. Same as it ever was.

—

Nihaar Sinha is a screenwriter and media/entertainment executive. From 2017 to 2019 he worked in the Content Strategy & Analysis group at Netflix. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.